We’re very excited about our new toy here at Everykey World Headquarters. We ordered an el-cheapo brand CNC router that we’re hoping to use to make cases for the Everykey and PCBs for new prototypes. While buying cheap hardware in China has some advantages (such as apparently including an AutoCAD license for free on the CD…), there are some drawbacks to consider:

- You’re obviously not going to be sure of the quality you’ll be getting. One generally prefers a solid and stable machine milling parts in sub-millimeter accuracy. So far, we’re impressed by the mechanical robustness. Everthing seems robust and was layed out quite “pragmatically” which served well to make the machine hackable. The included spindle, while usable, was the only part that we’ve had any concerns about mechanical quality – there’s too much backlash for accurate, even surfaces (however, results are still much better than 3D prints). Fortunately, the spindle turns out to be a Foredom H.30 handpiece ripoff with US standard flex shaft attachment, so it should be fairly simple to replace.

- The “english language” manual starts off with this reassuring gem: “Responding to be installed in the gas containing the explosive environment, otherwise have caused the explosive danger”

- The CNC controller only has a parallel port and we don’t have any computers from before 2000 laying around that have a suitable connection.

Opening the controller box reveals its quite shocking circuitry: It mainly consists of one Allegro A3977-based stepper driver board per axis, properly done with insulated inputs via optocouplers. That’s the good news (the A3977 is a very nice chip and optocouplers are a good thing to have if you’re going from logic levels to higher power domains). The bad news is that there’s another board between the parallel port and the stepper drivers, containing a line driver. It’s probably there to boost (some of) the parallel port signals to a level that can reliably drive the optocouplers. Unfortunately, this board is powered by the controller, nullifying the galvanic insulation and therefore rendering the optocouplers quite useless. We’ll address that later – for now, we will use it as is, very carefully.

Off-the-shelf USB-to-Parallel adapters don’t work for controlling CNC mills: The parallel port pins send step signals directly to the stepper controllers. For usable speeds, you need precisely timed signals with 10 KHz or more. That’s too much for ordinary converters because of the fixed 1 KHz framing of USB (these high frequencies are even a challenge for PCs, so CNC CAM applications usually need to use tricks to make it work, i.e. make use of low level timers for driving the parallel port).

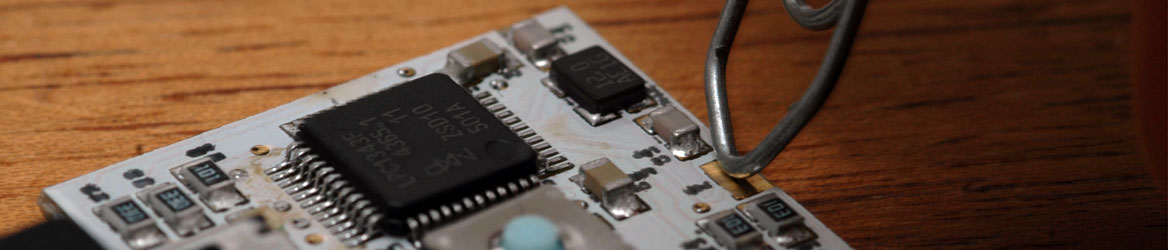

Hence, in order to talk to our CNC mill, we had to do something. Fortunately, we had some Everykeys and line drivers laying around to solve that problem (the purpose of the 74HCT244 line drivers is to shift the voltage levels from our 3.3V to 5V found at parallel ports). We have two options: a) Talk directly to the stepper driver boards or b) talk to the parallel port. For now, we decided to take the second option as it would also work for other CNC machines without modification, despite the “interesting” circuit mentioned above. Later on, we might replace that part with our solution to provide both USB connectivity and electrical safety (our line drivers can deliver enough current for the optocouplers, so the board is not needed any longer). This will also enable us to make use of the fourth axis which came with the machine: There are four stepper drivers, but the fourth axis is controlled by parallel port pins that cannot be driven easily by PCs.

The host does not control the steppers directly, but sends higher level motion commands to the Everykey, which takes care of stepper controlling and reporting the CNC mill state back to the host. Right now, we’re running at 20KHz, but there seems to be plenty of headroom for more.

Within a week, we were self-hosting. Here’s a picture of the elegant casing we made for our USB to Parallel Port adapter:

… as well as some shiny, acrylic glass Everycases:

Currently, we’re controlling the device via USB HID, which is working out quite nicely. We’re still using a roll-your-own scripting language, but are hoping to be able to import G-Code soon at the very least.

For the truely painless, there’s some code available for perusal in a secret hidden branch under the `examples` directory of the SDK. The host side of the project is still in such a pre-alpha stage that even we’re ashamed to release it. We’re working on controller software in Objective-C/Cocoa and node.js, fairly obvious plattform choices for interfacing to hardware 🙂